“No Studying Allowed?” – How Women Fought for Their Place in the Lecture Hall

At the end of the 19th century, the idea that women could pursue higher education was considered an affront by many in Germany. While female students were already attending lectures in the US, France, and even Switzerland, women in Germany were still denied access to higher education. But resistance began to stir in Karlsruhe – and it came from the women themselves.

First steps toward equal rights

As early as 1885, a private painting school for women was founded under the patronage of Grand Duchess Luise, since women were not permitted to attend the state-run Academy of Fine Arts. Two years later, following a resolution by the Karlsruhe municipal council, women were allowed to attend lectures at the Technical University as guest auditors – but only in art history and literary history. Clara Immerwahr, a chemist with a doctorate and wife of future Nobel Prize laureate Fritz Haber, gave public education lectures on “Chemistry in the Kitchen and the Home.” Although the topic reflected traditional gender roles, it marked an initial step toward scientific participation.

The breakthrough – finally enrolled

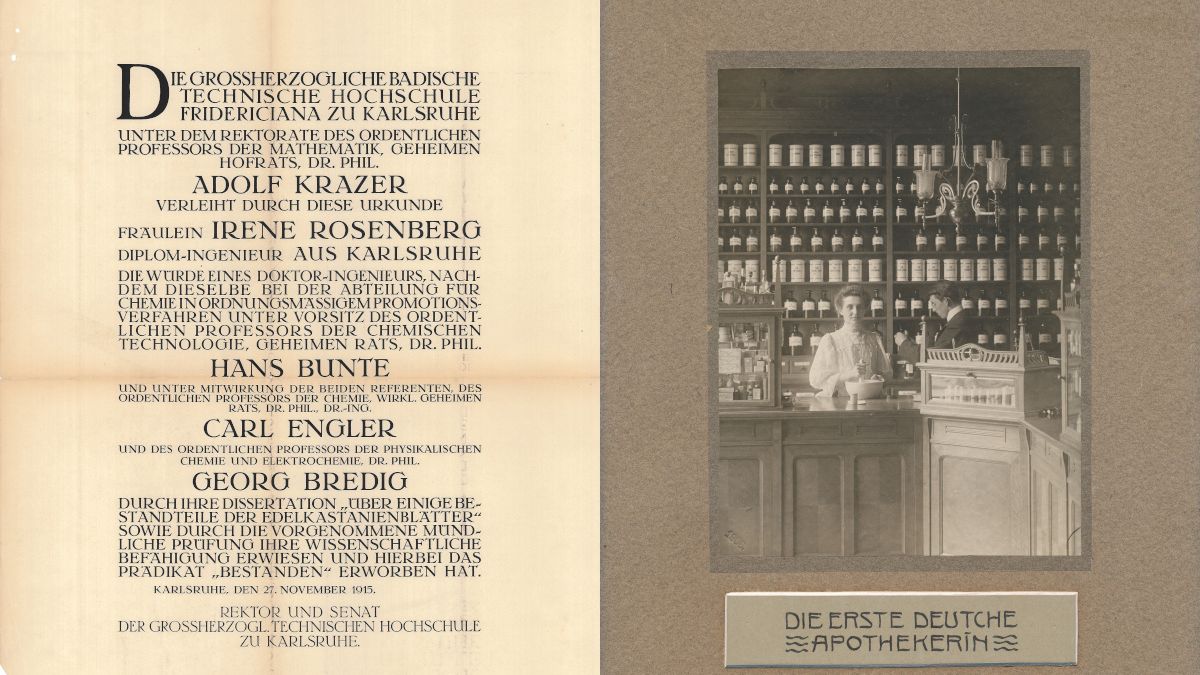

The turning point came in 1900: the state of Baden allowed women to enroll in university on a trial basis. Johanna Kappes from Karlsruhe was among the first women to be officially matriculated. Her fellow student Magdalena Meub later became Germany’s first licensed female pharmacist, and Thekla Schild became Baden’s first female graduate engineer. In 1915, Irene Rosenberg became the first woman to earn a doctorate at the Institute of Chemistry.

Yet the path to academia remained difficult for women: in the 1920s, they were still a rare presence at the Technical University. Under National Socialist rule, women were pushed back into the domestic sphere: in 1934, restrictions on university admission, compulsory labor service, and a dramatic decline in female student numbers were introduced.

A slow awakening

After World War II, women gradually returned to the Technical University. But it was not until the 1960s that their numbers began to rise noticeably. The social transformations of the time – broader access to education, new career paths, and growing youth self-confidence – were also reflected in the lecture halls. In 1970, women made up eight percent of the student body; by 1980, the figure had risen to over 14 percent. The doors were open, but many women still had to fight for their place.

Today, women account for around 29 percent of KIT’s student population. The first female professor, Dagmar Gerthsen, was appointed in 1993. By 2022, 18 percent of professorships were held by women. The fight for educational equality has borne fruit – and is far from over. KIT is now actively committed to equal opportunity and diversity: “At KIT, we are proud of the close ties between students, alumni and alumnae, researchers, instructors, and staff, because our diversity is our strength. It is not only a given, but also the driving force behind creativity and innovation,” said Jan S. Hesthaven, President of KIT, in his speech marking the 200th anniversary.

mex, August 14, 2025