Elementary Particle and Astroparticle Physics

What do neutrinos, the so-called ghost particles, weigh? What emits the energy-richest particles of the universe? Black holes? Neutron stars? Active galactic nuclei? And how is the universe structured? Such questions are studied by KIT scientists conducting experimental and theoretical research at the interface of astrophysics, elementary particle physics, and cosmology and the corresponding academic education. This also includes large international collaboration in fundamental research. KATRIN, for example, weighs neutrinos, the most abundant massive particles of the universe. The Pierre Auger Observatory is searching for the highest-energy component of cosmic rays.

Educating young scientists also plays a central role. The Karlsruhe School of Elementary Particle and Astroparticle Physics: Science and Technology (KSETA), offers doctoral students an excellent research environment and structured qualification program.

Research Focus

Elementary Particle and Astroparticle Physics

![]()

Elementary Particle and Astroparticle Physics, as well as related high technologies, have long been among KIT’s particular strengths. Our research spans both experimental and theoretical domains, ranging from fundamental research to the development of complex technologies. Key areas of focus include collider and flavor physics, high-energy cosmic rays, neutrino properties, and the search for dark matter. We are also pioneering novel and sustainable concepts for detectors and accelerators, extending to complex, integrated systems.

KIT is home to several world-class research infrastructures such as the GridKa Data and Computing Center, the Karlsruhe Research Accelerator KARA, and the KATRIN experiment. These facilities provide a strong foundation for excellent research and foster international collaborations in one of the most dynamic fields of modern physics. A recent highlight is the KATRIN experiment’s achievement in setting a new upper limit of 0.45 eV/c² for the neutrino mass. Moreover, KIT researchers play leading roles in major international collaborations, including the CMS Experiment at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider and the Pierre Auger Observatory in Argentina.

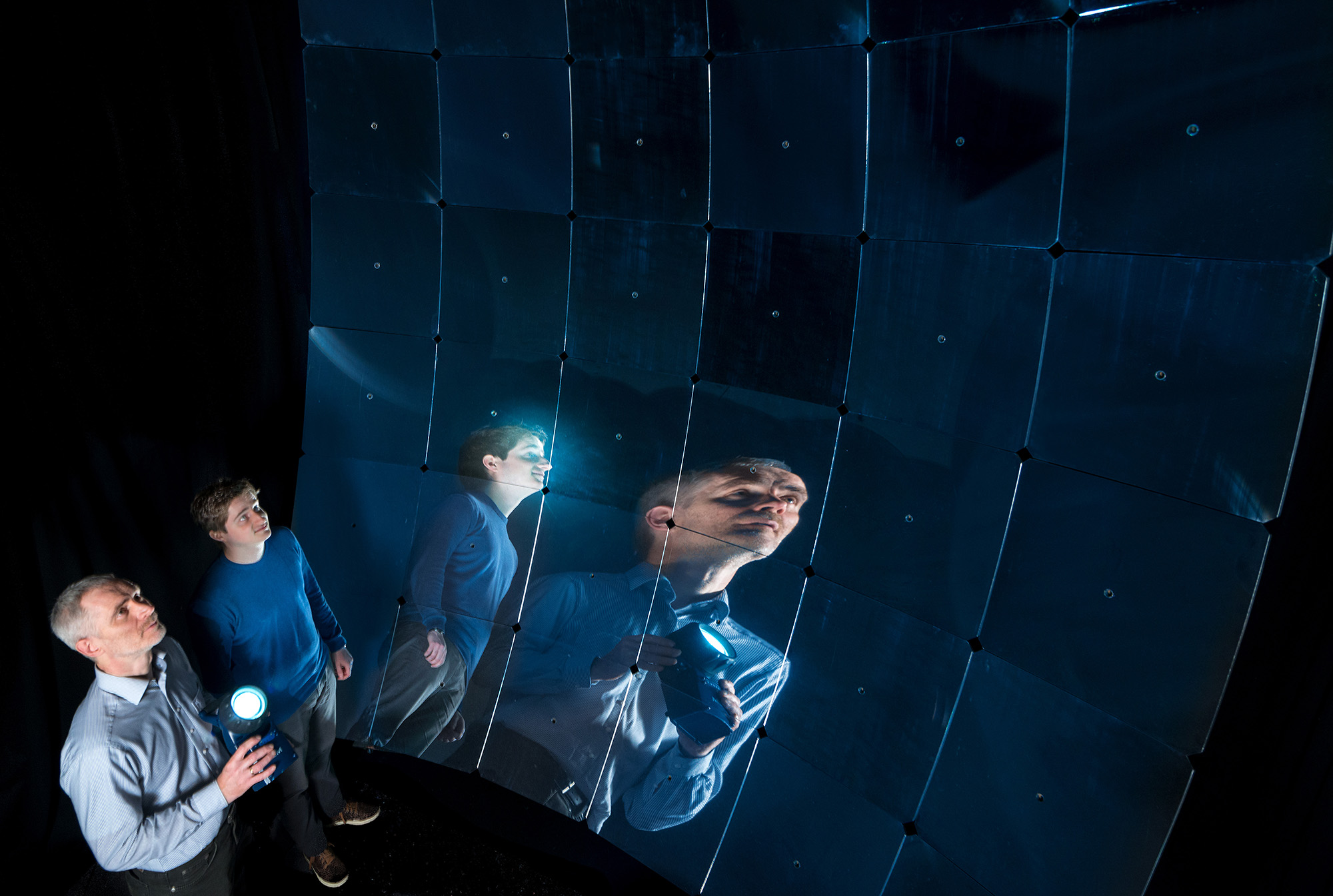

New Upper Limit for the Mass of Neutrinos

In April 2025, the Karlsruhe TRItium Neutrino Experiment (KATRIN) collaboration published new findings on neutrino mass. Based on the latest data, they established an upper limit of 0.45 electron volts/c2 (corresponding to 8 x 10-37 kilograms) for the neutrino mass. Compared to the previous results from 2022, the researchers nearly halved the upper limit. KATRIN, which measures neutrino mass in the laboratory using a model-independent method, has once again set a world record. This achievement was made possible by six times higher statistics, a 50 percent reduction of the background level, and significantly improved systematic uncertainties.

Uncovering the Secrets of the Universe

KIT is actively involved in of the world’s most powerful particle accelerators, including the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Switzerland. The LHC recreates conditions similar to those that existed about 10 to 12 seconds after the Big Bang. One of its four major detectors, the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS), is designed to study these reactions in detail. KIT research teams contribute significantly to the CMS collaboration, leveraging state-of-the-art machine learning tools to fully exploit this dataset. KIT scientists lead studies on the properties of the Higgs boson, measure extremely rare processes, and search for physics beyond the Standard Model – such as for hints of dark matter. In parallel, KIT is actively engaged in the preparation of the CMS detector upgrade for the high-luminosity phase of the LHC.The new CMS tracking detector is scheduled for completion in 2026.

The Mystery of Cosmic Rays

Researchers at KIT have significantly advanced our understanding of cosmic rays at the highest energies by analyzing data from the surface detector field of the Pierre Auger Observatory in Argentina. These observations aim to identify the sources of the universe’s most energetic particles and uncover the mechanisms behind their acceleration. Because of the extreme particle energies involved, the data allow scientists to explore physical laws under conditions that cannot be reproduced in any laboratory. They also provide a way to test theories about space-time fluctuations and the existence of extra dimensions.