200 Years of Pioneering Spirit: Scientific Progress and Ethical Responsibility

The name Fritz Haber represents a duality of progress and destruction: groundbreaking scientific achievements and the devastating consequences of their misuse. The chemist conducted research and taught in Karlsruhe from 1894 to 1911, revolutionizing agriculture in the process. Yet later, he turned his talents to war research and helped develop chemical weapons.

The Agricultural Breakthrough

In 1904, Fritz Haber began working on synthesizing ammonia. At the time, many scientists were searching for a way to artificially produce this pungent gas, as ammonia had proven to be a highly effective fertilizer—particularly when combined with sulfuric acid. With rapid industrialization, Europe’s population was booming—Germany’s had more than doubled to 55 million by 1900—and agriculture needed to keep up. However, natural fertilizers like animal manure were becoming increasingly scarce. Synthesizing ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen seemed promising, but no one had succeeded yet.

Breakthroughs: Pressure, Heat, and Industrial Scale-Up

The key to success came through an innovative combination of high pressure and high temperature. In the spring of 1909, Haber experimented with unusual catalysts like osmium and uranium. Using a newly developed high-pressure apparatus—featuring cone valves, which hadn’t existed before—he finally succeeded. At 185 atmospheres and temperatures between 600 to 900 degrees Celsius, ammonia began to form as a liquid in the lab.

Translating this lab discovery into industrial-scale production was the work of engineer Carl Bosch. At BASF’s labs in Ludwigshafen, Bosch and his team ran tens of thousands of experiments. They eventually discovered a catalyst that was effective, durable, and affordable: so-called "dirty iron," a form of iron blended with potassium oxide and other impurities to boost catalytic efficiency. This became the standard industrial catalyst for what became known as the Haber-Bosch process.

From Fertilizer to Ammunition – and the Deadly Use of Poison Gas

Haber’s story illustrates how scientific progress can present serious ethical challenges. During World War I, the German Empire relied on the Haber-Bosch process to manufacture explosives and ammunition. Ammonia was used to make nitric acid, which could then be turned into saltpeter using bases. When the Allied naval blockade cut Germany off from natural saltpeter sources in South America, synthetic ammonia became essential for continuing the war. This shift caused severe fertilizer shortages and crop failures, leading to the death of roughly 800,000 Germans from malnutrition during the war. As director of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin, Haber also led the development of poison gas. On April 22, 1915, near the Belgian town of Ypres, Haber—dressed in a chemist’s uniform of his own design—personally oversaw the first large-scale chlorine gas attack. Thousands of soldiers died, and a horrific new era of chemical warfare began. During the war, chemical weapons killed an estimated 92,000 soldiers and injured or maimed another 1.3 million.

Nobel Prize and Controversy

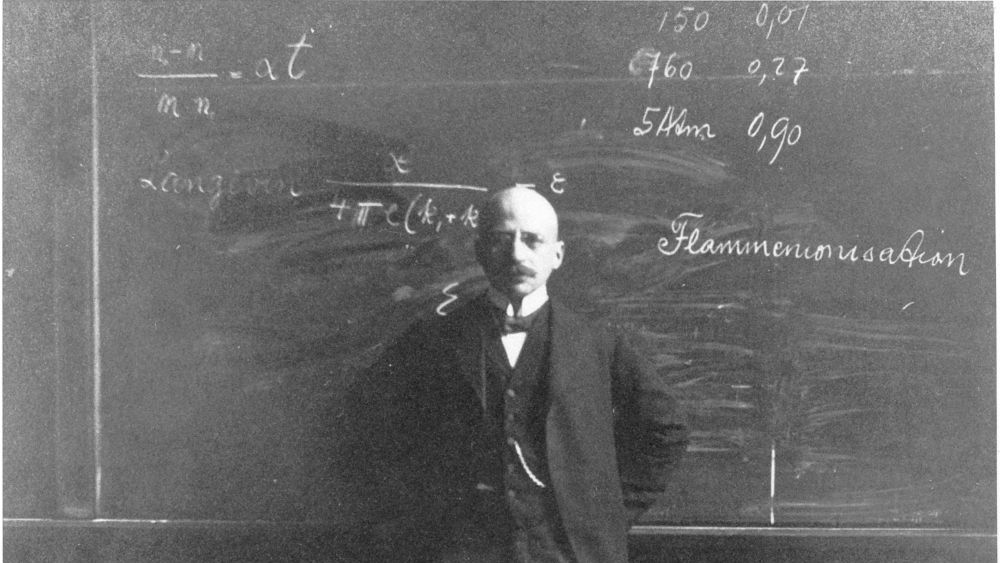

Fritz Haber’s motives remain difficult to fully grasp today: his life exemplifies that of a 19th-century intellectual citizen. The son of a merchant, he discovered his passion in science and built a reputation as a brilliant researcher and a dynamic teacher, admired for his sharp wit and deep commitment to his students.

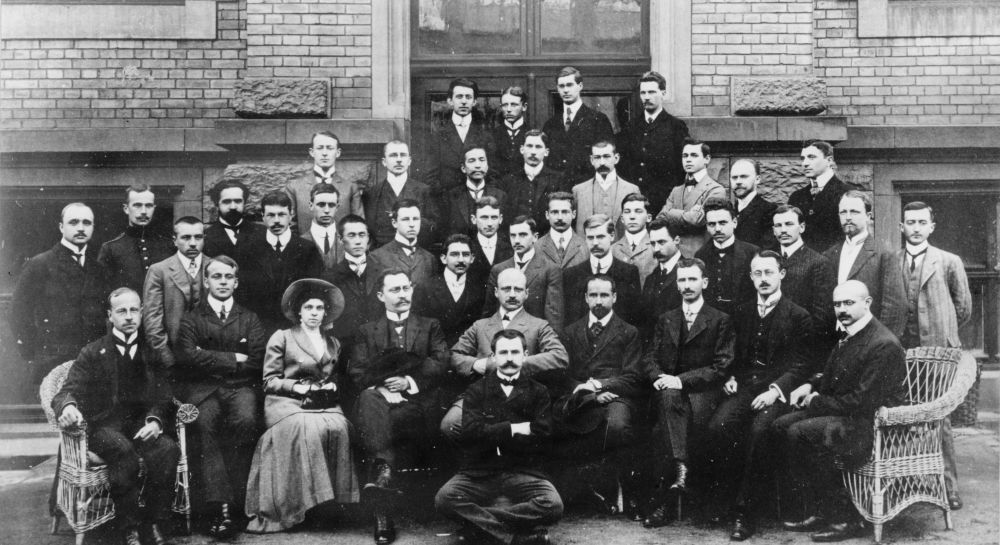

His lab in Karlsruhe was international, drawing scientists from Britain, America, Japan, and Eastern Europe. Among them were Robert Le Rossignol and Friedrich Bergius, both key contributors to high-pressure technology. Bergius and Bosch would later share the Nobel Prize in 1931 for their work in industrializing high-pressure technology. Haber was also part of the large Jewish community in the German Empire that believed they could demonstrate patriotism and earn full acceptance through service to the state and military. The irony is that in 1918—the year World War I ended—Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize for his development of synthetic ammonia, even as the Allied powers were seeking to prosecute him for war crimes related to his role in chemical warfare. His life remains a powerful example of the tension between scientific progress and ethical responsibility.

June 16, 2025