Geothermal Energy: The Treasure at Our Feet

The energy turnaround only works with the heat turnaround. Geothermal energy in this regard is to become the workhorse for generating heat regeneratively and storing it. The latter is the goal of the DeepStor project, for which Professor Eva Schill and her team of KIT's Institute for Nuclear Waste Disposal (INE) make exploratory drills on KIT's Campus North.

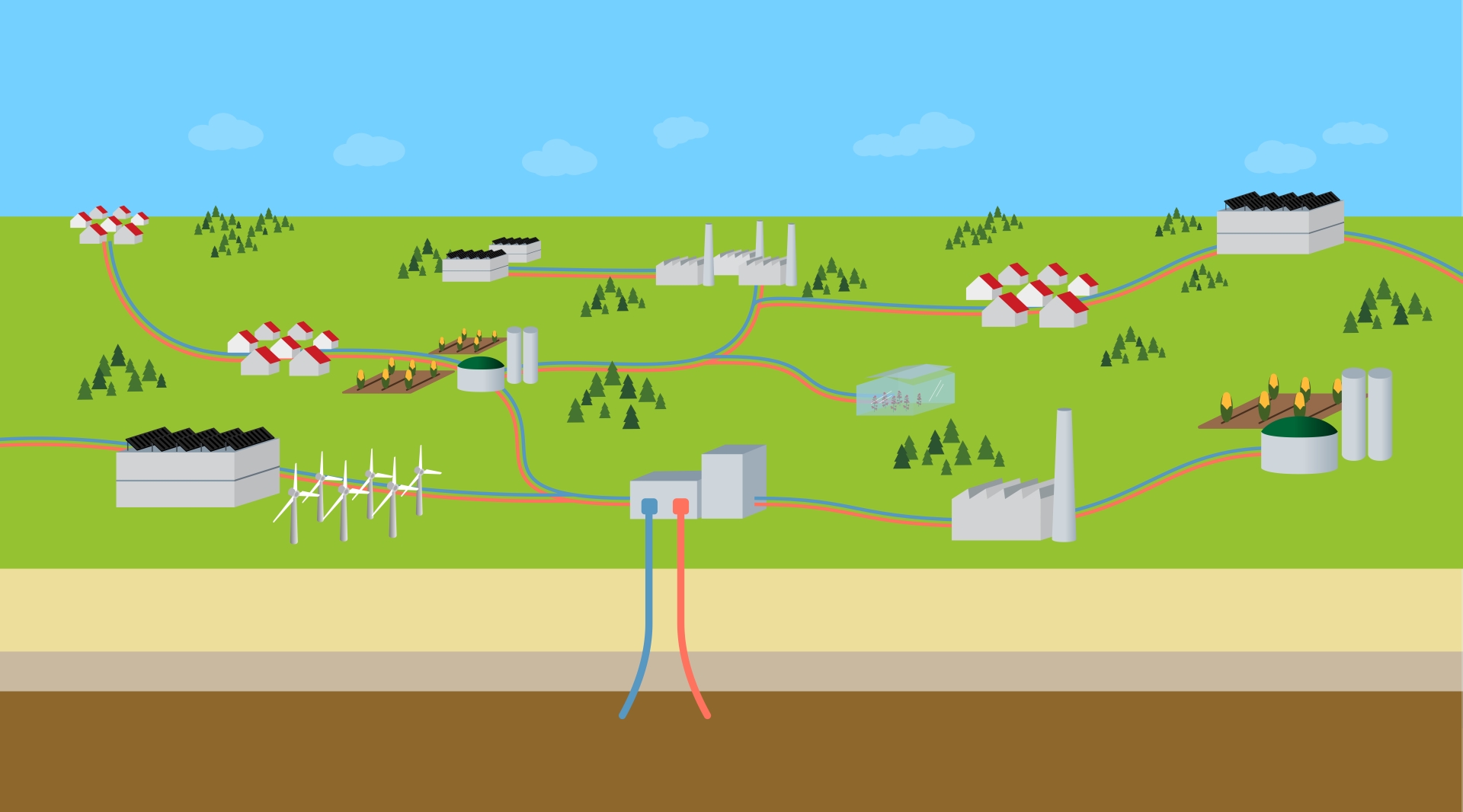

“With the technology that is currently available, a quarter of the German heat demand could be covered” Schill says, who researches at the KIT Institute for Nuclear Waste Disposal. The next technological generation could, as the geologist predicts, increase that amount to around 50 percent. “But we cannot only generate energy under our feet: We can also store it there.”

Efficient Heat Supply – Even for the Heating of Old Buildings

Schill is talking about so-called high-temperature aquifer storage systems that are an important component of her research. The idea to store heat underground is nothing new. The technology for this is already being used commercially in many countries. "But usually, one works in the low-temperature range of up to approximately 50 degrees Celsius," Schill points out. "We, in contrast, want to work in the temperature range of over 100 degrees Celsius."

This has several advantages. Many of Germany's district heating networks operate at a temperature of 110 degrees Celsius. High-temperature aquifer storage could be seamlessly integrated into the relevant processes. High temperatures are also putting less strain on the structure of the buildings connected to the heat network, allowing even old buildings to be efficiently supplied with heat.

Deep Underground Salt as a Challenge for Heat Storage

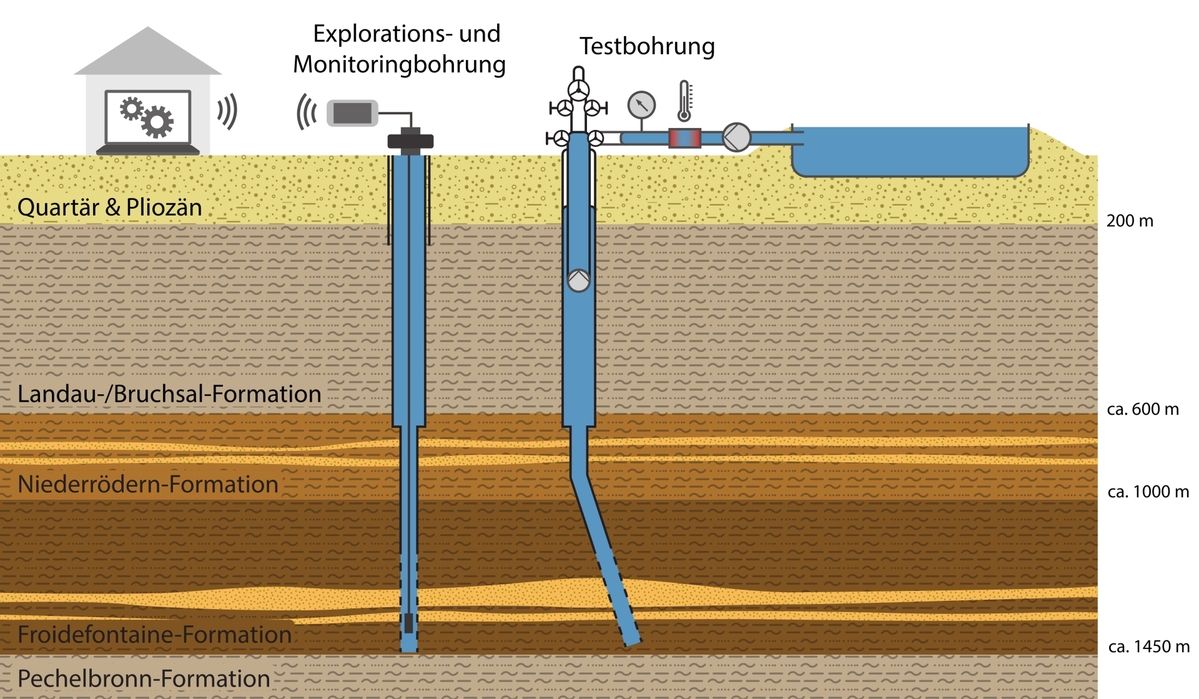

The DeepStor project is intended to advance storage technology. “One important question is how we can store efficiently,” Schill elaborates. To find answers, the first of two boreholes will be drilled on the grounds of KIT Campus North by the end of this year. The water found in the pores of the rock will be extremely saline and hot, as temperatures increase with the depth. One and a half kilometers under our feet, it reaches more than 100 degrees Celsius and the salinity increases rapidly. “Here in the Upper Rhine Graben, the salt concentration at the target depth amounts to more than 120 grams per liter”, Schill explains. This could turn out to be problematic.

The dissolved salts react to changes in their environment. If the temperature or pressure changes – for example, when heated groundwater is introduced for storage – it sets off chemical reactions. Salt deposits in the rock can dissolve, which on the one hand enlarges the pores of the rock and thus increases storage space. "On the other hand, it can cause precipitation,” the researcher points out. “This means dissolved salts becomes solid, which is negative for us because they clog the pores of the rock where we want to store the heated water." DeepStor is intended to show how to deal with this.

It will be a challenge worth addressing, Schill is certain of that. “Down there, we do not influence the groundwater that can be used as drinking water and there is a lot of space to store huge amounts of heat.” When generating heat from deep geological units, heat storage is also an important factor. “Deep geothermal energy generation should be operated continuously as turning it off and on changes the environmental conditions, potentially triggering malfunctions,” Schill says. Geothermal power plants will therefore also generate heat during the summer months when it is mostly not needed. It could then be stored inside high-temperature aquifer storage systems until the following winter.

Hannover Messe 2023

|

Aquifer Heat Reservoirs

|

Dialog with Citizens Is Essential

Among the population, geothermal energy is not always met with enthusiasm. Reservations and fears are circulating that frequently lead to public petitions – often regarding safe drinking water or the release of the radioactive radon gas that is located underground. Eva Schill and her team are aware of these challenges. They respond with dialog to questions from the public. “From the very beginning, we are involving the citizens in the project,” states Dr. Florian Bauer from Schill’s team. “We already involved the public in the licensing procedures for DeepStor and began co-designing with the surrounding communities.”

To demonstrate that it takes concerns like drinking water safety, a potential radon release, or induced seismicity seriously, the research team has launched a citizen science project together with other KIT researchers. "We equip participants with measuring devices," Bauer explains. Among these are seismometers and radon measuring devices. The researchers also monitor ground water measuring points.

According to the hydrogeologist, the collected data is incorporated into a computer model that allows him to produce a three-dimensional image that is displayed spatially by a special 85-inch monitor. “In this way, everyone can see what is going on in the depths and how their collected data contributes to making the project as transparent as possible.” Bauer elaborates. This system will be premiered at Hannover Messe 2023. Afterwards, several such monitors will be installed at central locations, such as the city halls of the relevant communities.

Kai Dürfeld, March 24, 2023

Issue 1/2023 of the research magazine lookKIT focuses on the highlights from technology development that KIT will show at the Hannover Messe 2023.

Magazine