“Now, we can rapidly and precisely design the ideal Petri dish for single cells,” Barner-Kowollik explains. Barner-Kowollik’s and Martin Bastmeyer’s team of chemists and biologists at KIT developed a new photochemical surface coding method. It allows for the precise modification of three-dimensional microscaffolds. “Customized structuring of adhesion points for cells allows for studying the behavior of individual cells in a close-to-reality environment,” Bastmeyer says.

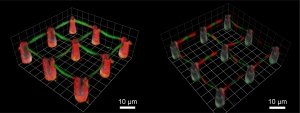

The Petri dish resembles a miniaturized ropes course. Its size is one fiftieth of a millimeter at the maximum. Isolated cells can be hung up between traverses and observed without any disturbing impacts. By an appropriate coating of traverses and poles, the cells are kept at the desired place and, if necessary, stimulated to grow. “In this way, we can study the motion and force of individual cells,” Bastmeyer points out.

To construct and coat the Petri dish with nanometer resolution, the cell researchers and polymer chemists use a direct laser writing method. Originally, this method was developed by the team of Martin Wegener from KIT for use in nanooptics. The three-dimensional scaffold forms at the points of intersection of two laser beams in a photoresist. At these points, the resist is hardened. For coating the scaffold, the team of Barner-Kowollik and Martin Bastmeyer uses various bioactive molecules and a photoactive group. Coupling is activated at the points illuminated by the laser beam only. There, bioactive molecules bind chemically to the surface. The physico-chemical properties and parameters, such as the flexibility or three-dimensional arrangement of cell docking sites, can be adjusted with a high local resolution when using these modern photochemical methods.

A whole set of photochemical surface coding methods is now presented by six publications in the latest issues of the magazines Angewandte Chemie, Chemical Science, and Advanced Materials. Using this set of methods, chemical bonds can be produced efficiently and in a locally controlled manner without catalysts or increased temperatures being required. Depending on the application, it is possible to maximize coupling efficiency, to accelerate the photoreaction, to directly couple to unmodified biomarkers, to reduce chemical synthesis work, or to design areas where no cell adhesion can take place.

References

[1] Pauloehrl, T.; Delaittre, G.; Winkler, M.; Welle, A.; Bruns, M.; Börner, H. G.; Greiner, A. M.; Bastmeyer, M.; Barner-Kowollik, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1071–1074.

[2] Pauloehrl, T.; Delaittre, G.; Bruns M.; Meißler M.; Börner, H. G.; Bastmeyer, M.; Barner-Kowollik, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9181–9184.

[3] Pauloehrl, T.; Welle, A; Bruns, M.; Linkert, K.; Börner, H. G.; Bastmeyer, M.; Delaittre, G.; Barner-Kowollik, C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9714 –9718.

[4] Pauloehrl, T.; Welle, A.; Oehlenschlaeger, K. K.; Barner-Kowollik, C. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3503–3507.

[5] Richter, B.; Pauloehrl, T.; Kaschke, J.; Fichtner, D.; Fischer, J.; Greiner, A. M.; Wedlich, D.; Wegener, M.; Delaittre, G.; Barner-Kowollik, C.; Bastmeyer, M. Adv. Mater. 2013, doi:10.1002/adma.201302678.

[6] Rodriguez-Emmenegger, C.; Preuss, C. M.; Yameen, B.; Pop-Georgievski, O.; Bachmann, M.; Mueller, J. O.; Bruns, M.; Goldmann, A. S.; Bastmeyer, M.; Barner-Kowollik, C. Adv. Mat. 2013, DOI: 10.1002/adma.201302492.

In close partnership with society, KIT develops solutions for urgent challenges – from climate change, energy transition and sustainable use of natural resources to artificial intelligence, sovereignty and an aging population. As The University in the Helmholtz Association, KIT unites scientific excellence from insight to application-driven research under one roof – and is thus in a unique position to drive this transformation. As a University of Excellence, KIT offers its more than 10,000 employees and 22,800 students outstanding opportunities to shape a sustainable and resilient future. KIT – Science for Impact.